U.S. broadband is about to face the tragedy of the commons.

If you live almost anywhere in the U.S., don’t expect to just “go remote” smoothly as your company is likely about to mandate you do. While remote work seems to be a magic bullet so far, that’s because less than 1% of us are doing it, and today at the dawn of the U.S. outbreak we already got brief glimpses of what to expect when 2, 5, 10% of the U.S. economy simultaneously goes remote.

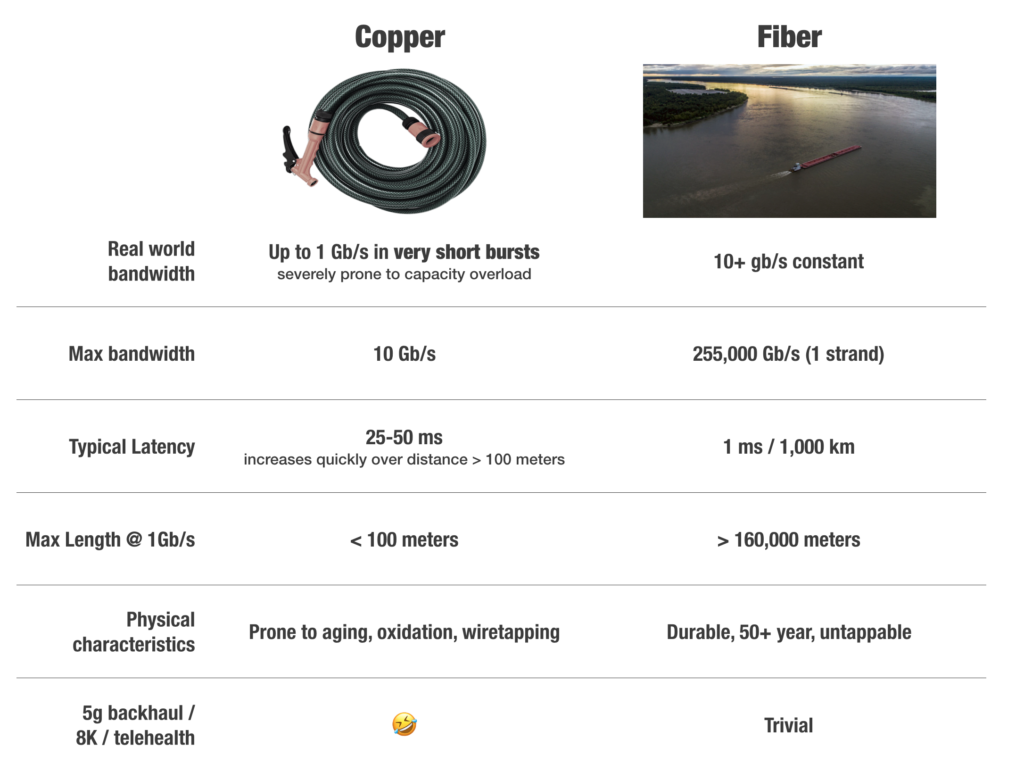

The problem is capacity required for remote work tools versus the physics of the dominant medium of U.S. internet connections: copper.

Why is our internet made of mostly copper? It’s because a handful of telephone and cable companies – the copper oligopoly – serve the vast majority of American internet subscribers. Just one problem: copper is awful at capacity. Advertised speeds can be faked right up to the legal limits surrounding truth in advertising, using lame hardware hacks and fancy footwork like Docsis. But you can’t fake the physics of capacity. Bandwidth-intensive services, like Zoom for team meetings and Netflix for chilling, gobble up capacity.

Lots of people are going to be trying to Zoom to work in the coming weeks. Because of that, our internet infrastructure is about to run up against the laws of physics. It will test our patience, and maybe our entire economy in the process.

Our dilemma isn’t unique to the internet. It’s one example from a well-known family of problems, the tragedy of the commons:

The tragedy of the commons is a situation in a shared-resource system where individual users, acting independently according to their own self-interest, behave contrary to the common good of all users by depleting or spoiling the shared resource through their collective action.

Wikipedia

Unlike most tragedies of the commons involving physical resources, where resource consumption is tangible, the digital version of this problem is largely invisible, knowable only by the symptoms of overwhelmed networks.

Remote work is great until everyone is doing it, or at least trying to do it. The sharp increase in video calls alone will overwhelm most incumbent last-mile networks at the local level in the U.S. And what will happen when most American universities run each day’s courses online?

Signs are already beginning to emerge. Calls aren’t going through. Connections are dropping out of the blue. Frequent lag and buffering. Service outages. Your favorite site seems slower than normal. Your super important Zoom team assembly can’t even right now.

Even stranger, many of the SaaS tools you rely on will seem suddenly buggy in unexpected ways. That’s because modern software as a service interacts constantly with the internet. While they may be relatively low bandwidth compared to heavy video, their requests to and from your client machine will be competing for the same amount of capacity they had available last week, with hundreds or even thousands of times the concurrent traffic next week.

For SaaS builders, suddenly, strange bugs that never existed before will begin to crop up in your products, and these bugs cannot be easily squashed, because they live just beyond the reach of your software engineers, out in the physical network. The only answer is carefully attending to graceful degradation.

None of this would be a problem, of course, if we had fiber to the premises throughout the U.S. But we don’t. Not even close. Less than 10% of the U.S. has what the FCC allows to be called fiber. Even many incumbent “fiber” customers are in for a bitter shock: during this crisis, they’ll learn what they’ve really been paying for: “fiber-esque” – a connection that isn’t fully fiber, but is marketed as gigabit speed, at a premium price, and is only as good as the weakest link out to the internet.

Video conferencing services like Zoom work like magic most of the time, in part because they have insanely talented engineers over there, and in part because there’s usually abundant bandwidth available to handle all simultaneous calls.

And yet Zoom could have the best engineers and the best systems on the planet, and your company could be among the thousands of organizations who are about to insist on remote video meetings, and not one bit of this matters if your Comcast connection – which is almost entirely copper – melts in the presence of the thousands of concurrent video calls going on all around you.

What’s going on? You might not think about it, but when you Zoom to remote work, you’re doing the digital equivalent of driving a huge, bandwidth-guzzling S.U.V. down what is almost certainly the digital equivalent of a two lane gravel road on your way to your team meetings. Good for you and your company. But what happens when all of your neighbors try Zooming, too? Less than 1% of the U.S. video conferences in daily work, and all of us already know the painful, stress-inducing symptoms of overburdened networks. What happens when 10% of our country’s workforce tries to video call during business hours? Who will you blame when your ISP makes you late for your remote work?

What about China?! They went remote…

Yes, China has been operating a remote-first, safety mode version of its economy for months now. That is possible, even at five times the population of the U.S., thanks to China’s extensive investment in fiber networks during the 2010’s. Now, even as most Chinese are quarantined at home, many aspects of modern Chinese life continue on thanks to reliable digital services. That smoothness absolutely will not happen in the U.S. during the coronavirus pandemic.

China invested in real information infrastructure: the fiber-extensive transmission, along with the edge processing and storage required to run advanced digital services such as streaming video calls, remote health, and remote classrooms.

Because they invested in real information infrastructure, China’s internet will, for the most part, not confront the tragedy of the commons at today’s usage requirements (which continue growing exponentially).

The U.S. did not make such investment. Even though the internet started here, it evolved in the U.S. over telephone lines, and later cable. Then, we let the staggeringly powerful copper oligopoly cajole us into remaining complacent, milking the public for tens of billions of dollars of subsidy along the way.

Personal prediction: the U.S. economy is going to fall even further behind during the Corona wave. Will we ever catch up?

Viewed from the bright side, the Corona pandemic may provide opportunity to reboot our economy to be digital-first. American telecom marketing 💩 is finally about to be exposed. Watch as your “premium” 300mb/s “fiber”* connection shudders under the weight of its true nature. Get ready to ask for refunds. Better yet, switch to your local internet service provider, if you’re lucky enough to have one, since their network is likely better than the cable company you probably get internet through today.

Want more info on the real state of U.S. broadband?

- Karl Bode tracks the U.S. telecom industry closely, and wrote an excellent primer on the subject of coronavirus last week.

- Chris Mitchell and team at ILSR’s MuniNetworks track U.S. broadband deployments and best practices.

- Drew Clarke and team at Broadband Breakfast track U.S. broadband policy.

- Broadband Communities is the go-to for community-driven broadband.

- Benton_inst

- NextCentCit

- EFFFalcon

- Gigibsohn

- Anyone else I should add? Please ping me hi at jase dot fyi or @jase on twitter